Day Trip to Cologne

Date

November 17th

Museum Ludwig, Cologne and ArtCologne

There are multiple ways to exhibit and to present art. Whether it be in a white cube, in a solo or group exhibition, digital, analogue and cross-media, or on-side works in public space – the form of presentation is highly dependent on the piece itself. But lately, another parameter has become relevant when planning an exhibition: sustainability. The environmental effects of art production and art presentation are more and more taken into consideration in the whole process of creating art; starting with an idea, becoming a concept and eventually a reality.

On their daytrip to Cologne, the Borderland group was confronted with two very different approaches on exhibiting art. With “Grüne Moderne”, the current show at Museum Ludwig, and the annual art fair ArtCologne, the extremes could not have been any more evident.

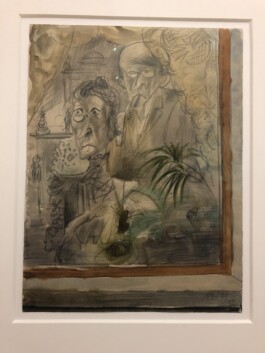

For the past few years, Museum Ludwig has experienced an in-house debate on how to act more sustainably as a museum. What started as a working group within the museum has now been implemented in the exhibition “Grüne Moderne. Die neue Sicht auf Pflanzen”, curated by Miriam Szwast. The exhibit focusses on plants in the early 20th century, a period in which plants had become a constant inventory of many households. Oftentimes exotic and tropical, they can be found on photographs, drawings, paintings and texts from that time. But back in the early 20th century, the hype also prompted deeper considerations on what a plant actually is: Is it just a decorative, sometimes edible material? Or might a plant actually be considered an animate being rather than “just a thing”?

The topic of “Grüne Moderne” was the perfect match for the museum’s long-planned sustainability agenda. By minimizing their use of materials (like wrappings and packages, print products, flyers and posters), they were able to reduce their waste significantly. They also reduced exhibition-related transports to a minimum, thereby emitting less CO2. Forgoing the usual procedure of shipping artworks around the world, they instead worked almost exclusively with pieces from their own collection and printed simple replicas of works that they did not have available. More examples of their sustainability efforts can be found in the catalogue which was not printed, but is available online and for free (hosted on an eco-friendly server). They also created an open workspace at the entrance of the museum where visitors are invited to continue on the museum’s research: they can find books on the topic, or add drawings to a “plant gallery”.

Curator Miriam Szwast welcomed the Borderland Residencies group at the museum and gave an introduction and a tour of the exhibition.

The museum’s conviction to take on responsibility for a more sustainable world made an impression on the group – as well as the consequences of that self-commitment. The low-key aesthetic of the exhibition as well as the renouncement of loaned art works did not sit well with all of the museums’ patrons. Although they did gain new, especially younger visitors, they lost the approval of some of the regular audience. Also the question remains of how this new concept can be applied to the following exhibitions. Still, Museum Ludwig made an effort to tread a new path, and the journey has only just begun.

After spending the morning at Museum Ludwig, the group later proceeded to ArtCologne, the annual Cologne art fair. While the encounter in the museum gave the impression that implementing sustainable goals into exhibition-making was complicated, visiting the art fair revealed a whole new complexity. Waste, CO2 emissions from transporting the artworks and the visitors, and non-reusable materials for building the booths are just a few of the issues that make sustainable fairs such a big challenge. Looking for cues on how to approach the subject, the Borderland group stopped at the booth of Cologne’s Temporary Art Gallery. Polish performance artist Adam Ritzke had been invited to show his “trashformance” at their booth: he collected waste that was produced during the fair and used it to create an extravagant costume. Complete with a crown, cloak and sceptre, he walked and floors of the fair with an almost royal attitude – a king clad in garbage. His aim to deconstruct concepts such as trash and royalty, matches well with the Temporary Art Gallery whose director Aneta Rostkowska has long been researching the relationship between humans and nature. She claims that every organism should be treated with equal political rights and negates the superiority of humans over other lifeforms.

There hardly is a place left on this earth that is not defined by human life. That fact is in no way reversible – there is a reason why geologists call our age the Anthropocene. And even though global politics and industries often make us feel like our path to environmental destruction is prescribed – people who work in art and culture can still choose to take another path. They can still try to make an impact in a system that otherwise seems unshiftable by proofing that within their own line of work, changes can be made.